Taos Puebloans surface mined on a very small scale for nonmetallic substances — such as clay for pottery, ocher for pigments, and various rock types for arrowheads — and prior to 1680, Catholic priests purportedly mined gold, silver, and copper in Taos County, using slave labor. Area Prospecting first began on an important scale after 1866, when rich gold placers were discovered at Elizabethtown. The Copper King copper mine in Red River, initially worked in 1867, was the first known mine to be developed in Taos County.

Miners explored the nearby valley of the Rio Colorado (Red River), wandering the length of the river from its origin to its junction with the fabled Rio Grande. Rewards were minimal and interest waned, although the Red River Mining Company established a claim and build a smelter around 1879-80. Still, results were not cost efficient and it would be another ten to twelve years before serious efforts would be renewed in the area that would become Red River City.

As spring of 1895 saw the mountain snows beginning to melt, the air buzzed with human activity, the result of the discovery of shiny precious metals in the streams and rivers that flowed in the high country. Glowing accounts in The Raton Range, weekly newspaper of the railway town located on the old Sante Fe Trail on the front range of the Rocky Mountains, proclaimed the “Great Mining Camp of LaBelle,” a renewed interest in the fading gold fields of the Moreno Valley (in particular Elizabethtown), and the declaration that “Red River City is still booming.”

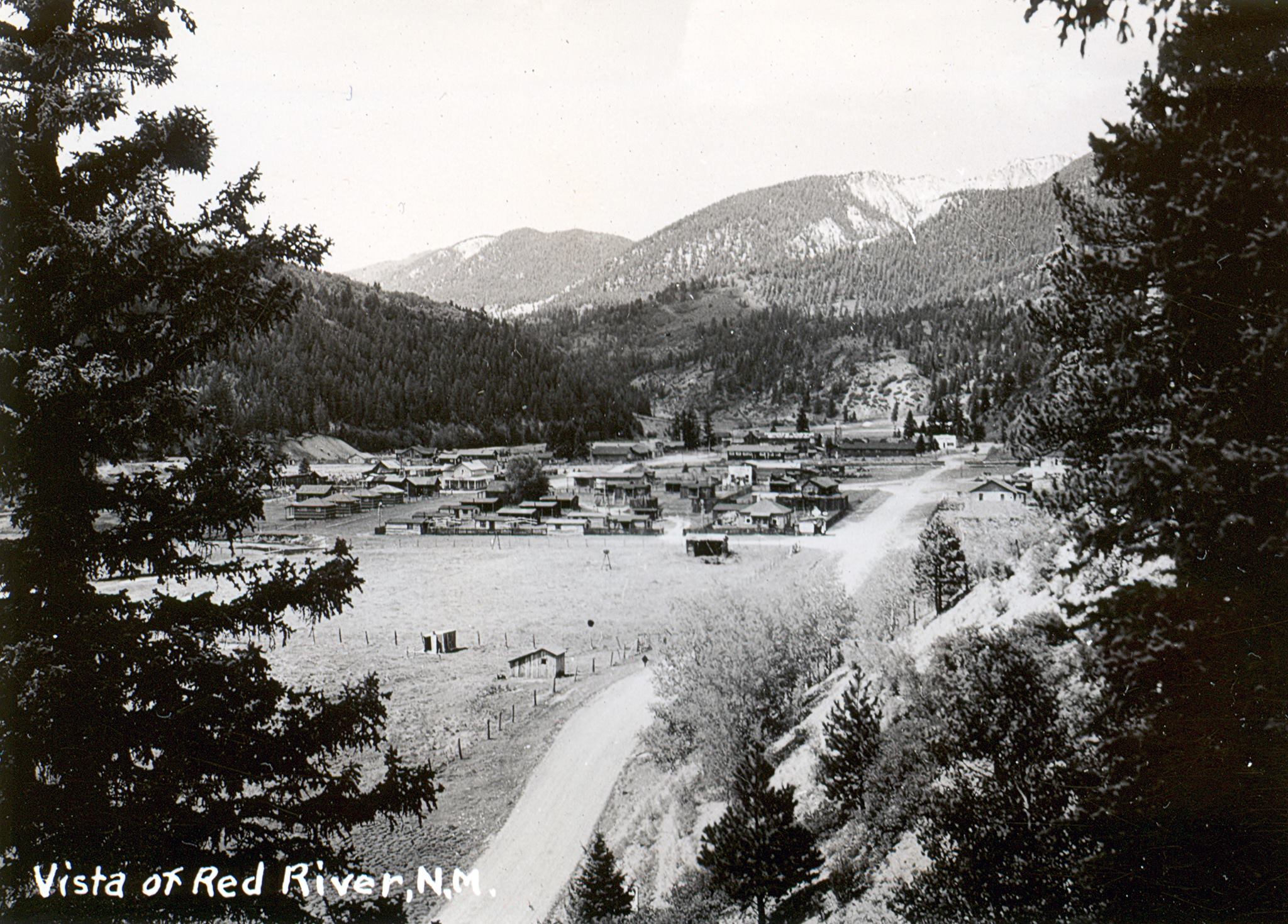

Red River City was taking shape on the banks of the river which gave the gold camp its name. Tents and modest, quickly-build log cabins were springing up throughout the valley. Within a year the crush of civilization would forever change the landscape from a pastoral place for grazing sheep into a noisy center of mineral exploration and development.

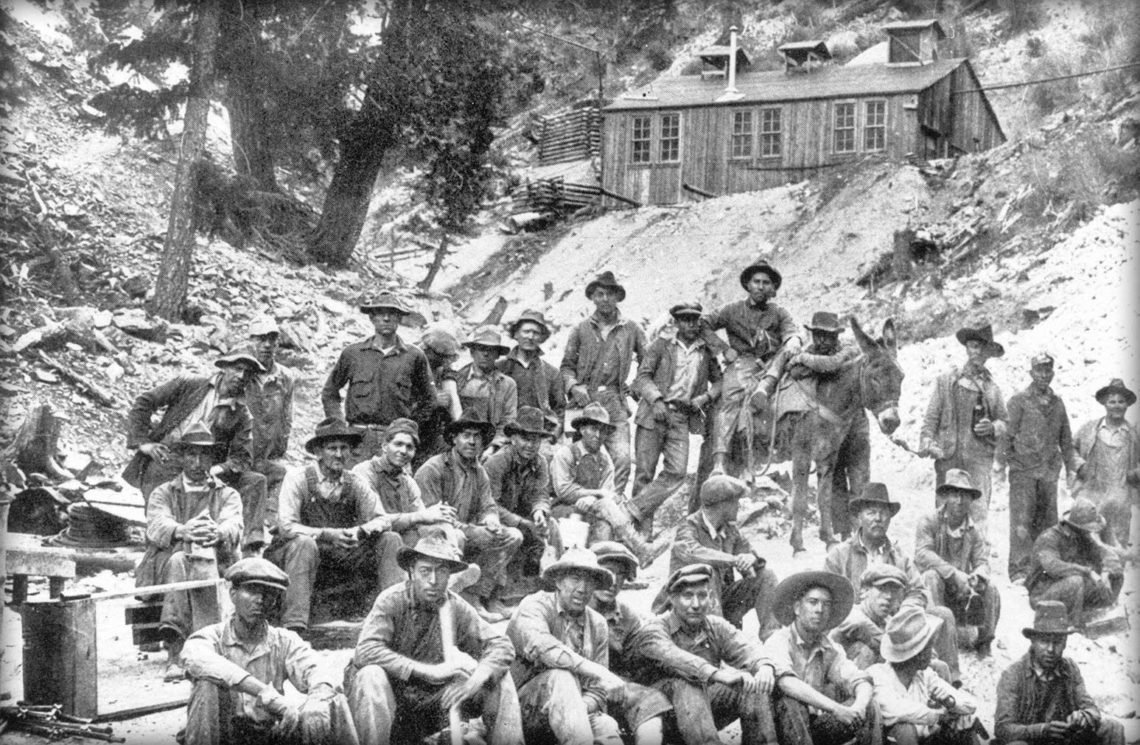

The pursuit of gold and silver dominated the flow of commerce. Names like Gilt Edge Placer, Golden Treasure, Junebug, Silver Queen, Jayhawk, Inferno, Independence and the Black Copper would stir the spirits of the rainbow chasers who came to the isolated valley in search of a future. Most of the seekers, however, were not professional miners but rather shopkeepers, school teachers, farmers and store clerks who had lost everything in President Cleveland’s recession and had nothing left to lose. Most didn’t even know what real gold looked like, mistaking the shiny pyrite for the real thing.

By the time Red River City got into the full sway of gold fever, the days of striking it rich with a glorious “find” were no longer the way to wealth for individuals in the mines of the American West. To discover a promising site was one thing, but to develop it properly required money. Large companies capable of investing working capital purchased the claims of hard rock miners. A good example was the 1897 sale by Harry Brandenburg of his share in the Black Copper. The $4,000 he received was sizable for the time, and the Black Copper only officially produced $200,000 in pay ore, but at great expense to the investors who eventually abandoned their investment.

The glory days of Red River City were brief. Low grade ore and costs of processing which required transportation to places like Pueblo, Colorado, proved to be anything but cost efficient. Add the hardship of hard rock mining which was complicated by ground water which flooded tunnels and shafts. By 1897 many miners had moved on to other gold fields, like Cripple Creek, Colorado and the Klondike in Alaska.

By 1905, the population which had once been touted as 1,500 to 3,000 souls dwindled to 150. Mining did not completely die in the area and a surge of interest preceded the outbreak of World War I, which generated some outside investment, most noticeably with the Buffalo Mine and the Caribel. The revival, however, did not survive the war and only a handful of hardy individuals like Pete Del Dosso and Carl Purkapile “kept the faith” of the hardrock miner and worked various prospects with little success.

Today, only traces of those glory days can still be seen, remnants of an exciting time in the history of the valley. The Red River of the 21st Century relies on providing hospitality, relaxation and a break from the ordinary. The pieces of the past, however, that can still be seen in the canyons and along the banks of the chilly mountain streams offer a chance to step back in time, a time so different, yet so like our own days of dreams and aspirations.

Note: The first paragraph is from the 1960 booklet, “Mineral Resources of Taos County, New Mexico” by John H. Schilling, published by the State Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources

The rest is written by J. Rush Pierce & Royce Raven. A slightly longer version appears on the Red River Miner website here.