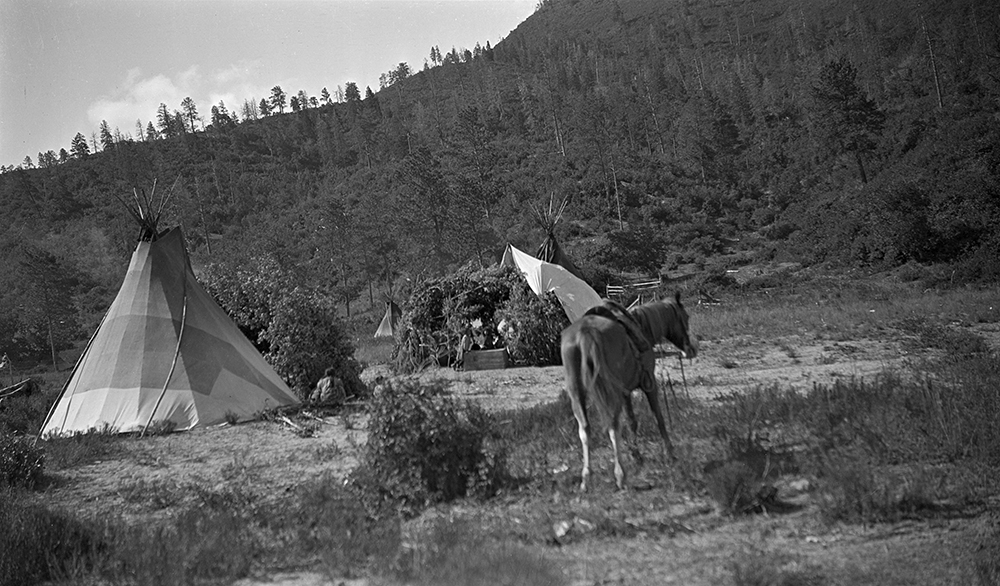

The Jicarilla Apache lived in a semi-nomadic existence in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, northern New Mexico, southern Colorado, and the Great Plains starting sometime before 1525. They lived a relatively peaceful life for years, traveling for hunting, gathering and cultivation along river beds. Taos is the center of their earth and for nearly 500 years they lived and died there. With their Taos neighbors, they fought the Spanish and, later, the Americans.

The Jicarilla world was populated with holy deities, including the sun and the moon, each of whom after their emergence near Taos produced a child with White Shell Woman, a young Jicarilla girl who was separated from her band. White Shell Woman gave birth to Naiyenesgani (Killer-of-the-Enemies) when the sun shone upon her, and also to Kubatc’istcine (Child-of-the-Water) while sleeping under the moon. The heroic adventures of Killer-of-the-Enemies and his brother Child-of-the-Water forms a major part of the Jicarilla creation narrative.

To the Jicarilla, the Rio Grande Gorge was etched into the earth by the horns of a giant killer elk that was speared and skinned by Killer-of-the-Enemies with the help of a gopher assistant and four differently colored flint-bearing spiders. This event began somewhere near Baldy Mountain east of Taos and ended in the gorge where the animal was slain.

The first Spaniards to reach this area, an exploratory party of Coronado’s expedition from Mexico, visited the Taos Pueblo in 1540. The Spaniards who first settled this area around 1615 lived near Taos pueblo, then Taos; however, as more people settled in the area, ill feeling increased until in 1631, a priest and two soldiers were killed by the Indians. In 1680 the pueblos banded together in a successful rebellion which drove the Spanish out of New Mexico. But their freedom was short lived. In 1692 De Vargas reconquered New Mexico, and the Spanish colony at Taos was reestablished.

The Río Colorados were mentioned with increasing frequency during the Spanish Reconquest in the 1690s. Dolores Gunnerson argues that the Río Colorados may have shared the Red River Country north of Taos with the Achos. Diego de Vargas, governor of New Mexico from Dec. 17, 1693 to Jan. 5, 1694, was told by his interpreters that the mountains that ran along the edge of the Red River were inhabited by the Achos during his 1694 campaign to reduce Taos Pueblo after the Reconquest. Soon after this, the Spanish began to refer to all of these bands as Xicarillas after the province they inhabited in north-eastern New Mexico.

La Xicarilla quickly became important as the last line of defense for the Spanish against Comanche and Ute raiders, who, backed by French arms, threatened the northern frontier.

Between 1704 and 1722, the Achos and Río Colorados fled their mountain strongholds on the heels of Ute aggression. Additionally in 1723, because of these ongoing hostilities and threats by the Comanches, the Jicarillas agreed to settle into pueblos, be baptized, and accept an alcalde mayor and mission, thus becoming Spanish subjects legally entitled to the protection of Spanish military forces. By the following year, most of the Apaches had moved into the colony at Taos

The mid-1800s until the mid-1900s were particularly difficult as tribal bands were displaced, treaties made and broken, and the Jicarilla Apache suffered significant losses due to tuberculosis and other diseases, and lack of opportunities for survival. By 1887 they received their reservation, which was expanded in 1907 to include land more conducive to ranching and agriculture, and within several decades realized the rich natural resources of the San Juan Basin under the reservation land.

Their most sacred shrines dot the San Luis Valley and are still visited by Apaches today.

The Ute

The Ute Mountain people once inhabited a vast expanse that included northern New Mexico. They migrated to the Four Corners region around 1300, and from there dispersed across the Rocky Mountains and into the Southern Rockies. The Utes were among the first indigenous people in North America to master the horse, which made them among the most feared and tribes in the Four Corners region. They carried out raids in northern New Mexico, stealing from the Puebloans, Jicarilla Apaches, Navajos and Spanish colonists, including New Mexico settlements from 1730 to 1750. Well into the 1840s the Utes attacked settlements in the Taos Valley and around northern New Mexico.

In the early 19th century, trading posts became part of the Ute landscape as French Canadian and American fur trappers and traders began arriving seeking beaver, otters, and other furs. Additionally, traffic brought on by the Old Spanish Trail opened up the Ute’s traditional territory to a flood of newcomers seeking land and resources.

In 1849, Ute chiefs signed a treaty that provided US citizens free passage through Ute territory and allowed for the establishment of military and trading posts. In exchange for these concessions, the Utes were promised presents and farming implements. The government hoped that persuading Native Americans to live a settled, agricultural existence might curb the raids. However, as settlement was forced upon them, they became increasingly hostile toward the government and settlers.

After violent conflicts between Utes and miners in Colorado, a treaty council was convened in 1863 in an effort to move Ute bands to the Four Corners area. Weminuche, Caputa, and Mouache bands refused to attend the council or sign the treaty.

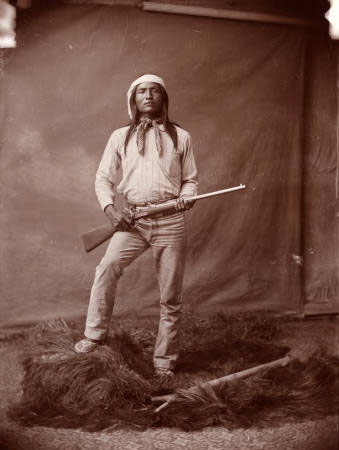

With reduced trade relations and diminished access to game, the Utes became increasingly dependent on the US government. In 1850, in agency was opened for the Utes at Taos. It was soon closed for lack of funds and it re-opened in 1853 with Kit Carson as its agent. Beginning in 1853, rations were being distributed to the Mouache in Red River and Arroyo Hondo and the Caputa on the Chama River.

Today, the Ute live on a reservation that spreads across southwestern Colorado, northwestern New Mexico and small sections of Utah.

Mountain Men

Although Spanish colonists carried on a lively trade in deerskins and buffalo hides in the Southwest, there is little evidence of significant trade in fine furs from 1540 to 1821.

Mountain men began arriving in Taos by 1750, and, with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the Mountain Man period began in earnest as fashionable, tall beaver-skin hats made beaver pelts profitable. Many mountain men lived closely with native people, adopting their dress and ability to live off of the land.

Around this time, the area around Red River was populated by hunters and trappers, mostly in the Midnight country. Taos became a base of operation and the Taos Trade Fair became even more popular. Mountain trappers would trade their pelts for supplies, and then would celebrate by courting Taos women, gambling, and drinking whiskey known as “Taos Lightning.” Most often, trappers would spend the winter in Taos before trapping again in the spring.

The fur trade declined in the 1830s as the beaver became scarce, and beaver skin hats gave way to silk hats. Mountain men turned to other pursuits, but many of them remained in New Mexico.

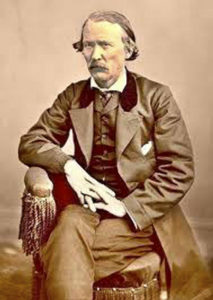

Kit Carson

Christopher “”Kit” Carson (1809–1868), the most famous of the mountain men in Taos, arrived in Taos in 1826. He was first married to an Arapaho woman named Waa-nibe and later married a Taoseña, Josefa Jaramillo, and fathered eight children. A man of his time, he is sometimes remembered as an Indian fighter, however he also fought for the Indian’s rights as the Jicarilla Apache Indian Agent. He spoke several Indian languages. His home is preserved as a museum on Kit Carson Road in Taos.

— by Ellen Miller-Goins

Sources

Ute History and the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe by James M. Potter in the Colorado Encyclopedia

Southern Ute Indian Tribe Chronology from the Southern Ute Indian Tribe website

The Jicarilla Apaches and the Archaeology of the Taos Region by Sunday Eiselt Morgan

Mountain man, from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia