The Enchanted Circle drive exhibits a spectacular combination of geologic features, including mountains, valleys, and volcanoes that attest to a long geologic history.

During the earliest part of Earth’s history (4.54 billion to 543 million years ago) rocks now exposed at the surface of Wheeler Peak were miles beneath the Earth’s surface. Then, beginning about 1.8 to 1.4 billion years ago, the landscape changed dramatically as continents drifted over the globe, occasionally colliding forming mountain ranges, or splitting apart, forming rifts.

Precambrian rocks found in the Wheeler Peak and Columbine-Hondo Wilderness Areas reveal the eroded, metamorphic traces of those ancient mountains.

About 1.7 billion years ago, a thick pile of sedimentary rock accumulated in a large ocean basin. These rocks were deeply buried and metamorphosed. Large granitic intrusions from about 1.4 billion years ago can be seen on Bobcat Pass and on top of Wheeler Peak.

By around 310 million years ago, the ancestral Rocky Mountains had emerged, leaving most of New Mexico submerged beneath tropical seas. These seas teamed with ancient life, and fossilized remains of hundreds of marine species of bivalves, snails, sea lilies, corals, etc., can be found around the Enchanted Circle. Although sedimentary rocks such as these were deposited at the sea bottom as horizontal layers, in our area these beds dip at an angle. At several different times beginning 286 million years ago, great mountain building events have folded and faulted the beds into their present positions.

Around 70 to 33.7 million years ago, tectonic upheaval shaped the “modern” Rocky Mountains and much of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Northern New Mexico’s Sangre de Cristo Mountains are located between the Rio Grande Rift to the west and the Raton basin to the east. The Sangre de Cristo Mountains of northern New Mexico include the western Taos Range and the eastern Cimarron Range, separated by the Moreno Valley. The Taos Range includes numerous peaks with summits between 12,000 and 13,000 feet, plus Wheeler Peak (at 13,161 feet, it is the highest point in New Mexico). Cimarron Range altitudes range from 11,000 to 12,500 feet. The floor of the Moreno Valley is 8,238 feet at the village of Eagle Nest and rises to well over 8,500 feet along its edges.

The Rio Grande Rift formed between 35 and 26 million years ago when the Earth’s crust began to spread apart, triggering volcanic activity in the region. The Rio Grande Rift split over 800 miles through Colorado, New Mexico, Texas and northern Mexico. Mountain streams carried sediments into this topographic low and from time to time, volcanoes to the west erupted, blanketing the gravels with lava, damming streams and creating temporary lakes.

About 3 million years ago the Rio Grande, with its ancient headwaters in the Red River Canyon, began to cut through the sediments and lava, forming the modern gorge. During the Pleistocene ice ages, glaciers covered the higher peaks and scoured out U-shaped valleys and arcuate depressions called cirques. Some time after 600,000 years ago the Rio Grande expanded its headwaters to the mountains in southern Colorado through the San Luis Valley.

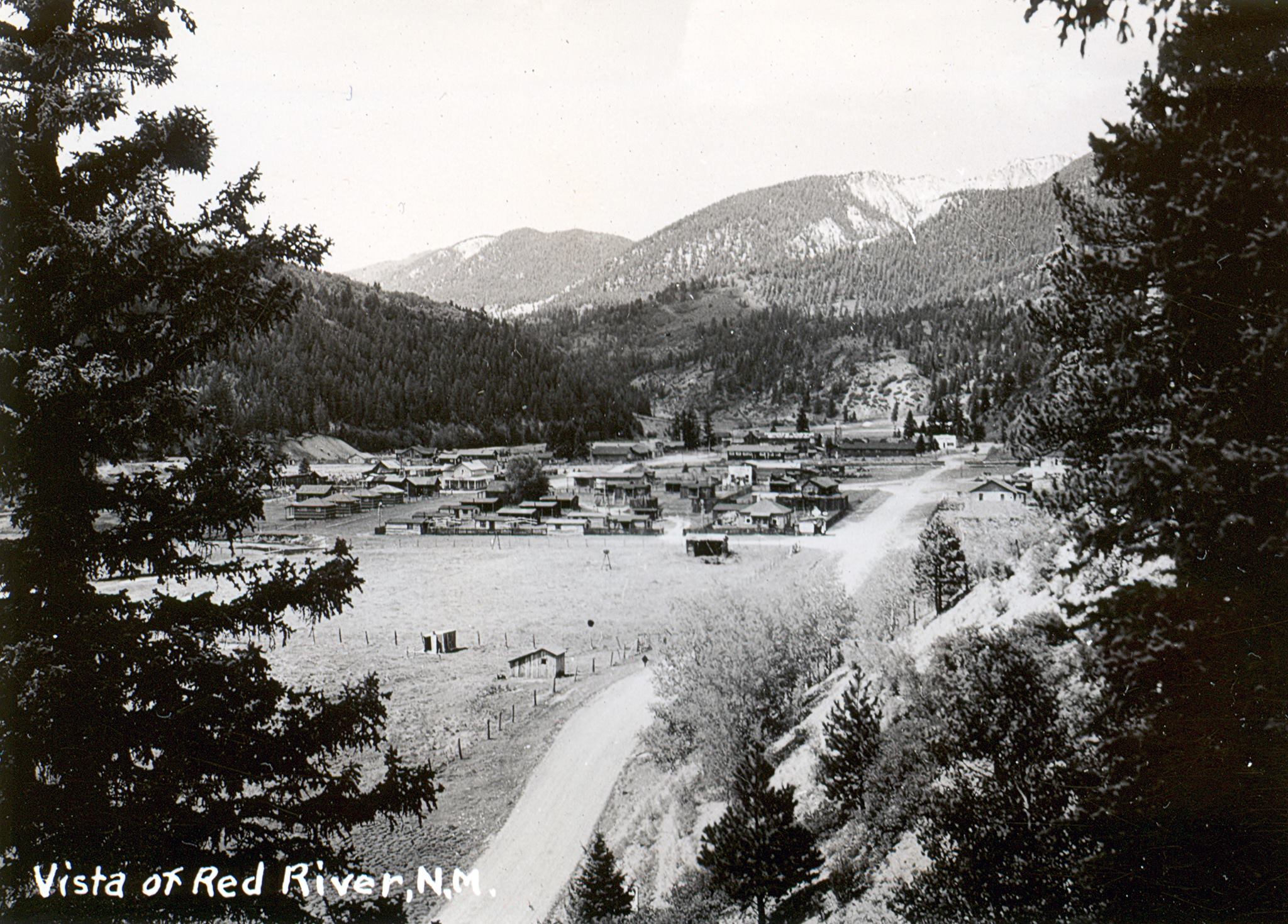

The town of Red River is in a deep fault valley on the southern edge of the Questa Caldera. About 25 million years ago a volcano, centered on what is now Latir Peak, blew up then collapsed, forming a caldera. The high ridge between the Red River and Cabresto Creek is composed of densely welded Amalia Tuff, which was explosively ejected from the Questa Caldera.

The circulation of hot mineralized fluids produced the profound “alteration scars” that line the valley and parts of the canyon between Red River and Questa. Rock under these areas was crushed, then hot water from below pushed to the surface through cracks, depositing minerals. As these minerals were exposed to air and rain, they decomposed and stained the outcrops yellow. Flash floods carry this loose material down side gulches into Red River Canyon in mud-flows (mixtures of water, mud, and gravel having the same consistency as wet cement).

Drive NM 38 into the canyon and you will cross several mud-flow deposits, and see many treeless, yellow-stained areas higher on the canyon walls. Heavy rain and subsequent dangerous mud flows often close the highway during the summer monsoon season in July and August.

Larger mudflows from the side gulches have formed “dams” across the Red River. Over many years enough mud has collected behind each dam of boulders to create a wide, flat, grassy meadow. These meadows are now the sites for most of the campgrounds along NM-38, as well as for the town of Red River.

NM-38 more or less follows the southern boundary of the Questa Caldera. Elephant Rock is actually a large block of quartz and latite that slid down from the southern wall of the Questa Caldera. The wall of the caldera to the south consists of Precambrian metamorphic rocks and granites overlain by Tertiary (between 25 to 2.6 million years ago) volcanic rocks.

The Bear Canyon pluton, one of many Tertiary bodies in the canyon is a spectacular example of geologic features left by Questa magmatism. This volcanic upheaval is also responsible for much of the mineable wealth in the area.

Midway through the canyon, visitors can see environmental clean-up efforts — all that remains of the molybdenum mine. The mineral molybdenite (molybdenum disulfide), an ore of the metal molybdenum (from the Greek “molybdos” for “leadlike”), is found in unusually high concentrations in this area. The soft, shiny, black, greasy-feeling molybdenite is found in veins and as thin “paint” in cracks along the edge of an igneous intrusion of the same type of granite as the Bear Canyon pluton.

During the Pleistocene Epoch (the past 1.8 million years) ice ages, separated by warmer periods, chilled New Mexico. During ice ages, glaciers covered the higher peaks and scoured out depressions called cirques. The Bull of the Woods glaciation began about 150,000 years ago. Red River-area mountain lakes, Alpine valleys and sculpted mountains reflect their sculpting. The resulting natural beauty brings many visitors to Red River but the town owes its existence to 1.8 billion-year-old Precambrian rocks, the oldest exposed rocks in the state, many of which contain gold, silver and copper.

A gift from the past….

— by Ellen Miller-Goins

Note: Thanks to Dr. Matthew Zimmerer, Field Geologist II with the New Mexico Bureau of Geology & Mineral Resources at the New Mexico Institute of Mining & Technology for his invaluable advice.

Sources:

The Geology of Northern New Mexico’s Parks, Monuments, and Public Lands by Price, L. Greer, sold by the New Mexico Bureau of Geology.

Scenic Trips to the Geologic Past No. 2: The Enchanted Circle loop drives from Taos, by Paul W. Bauer, Jane C. Love, John H. Schilling, and Joseph E. Taggart, Jr., published by New Mexico Bureau of Mines & Mineral Resources.

Geology of the Taos Area: Geologic History, a summary of training given in 1999 in Taos, New Mexico, to Astronaut candidate teams by JSC/NASA (Johnson Space Center, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Manned Spacecraft Center) and the New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources (NMBGMR), a division of New Mexico Tech.

An excerpt from Another Time in This Place: Historia, Cultura y Vida en Questa(2003) by Tessie Rael y Ortega and Judith Cuddihy.

Geo•ski•ology: Red River Ski & Summer Area by Virgil W. Lueth, from Lite Geology Spring 2017, published by the New Mexico Bureau of Geology & Mineral Resources